Studies in the storm

Hundreds of tests performed every week in the one-of-a-kind Volvo Cars wind tunnel determine the future of automotive design. Step inside to brave the blast.

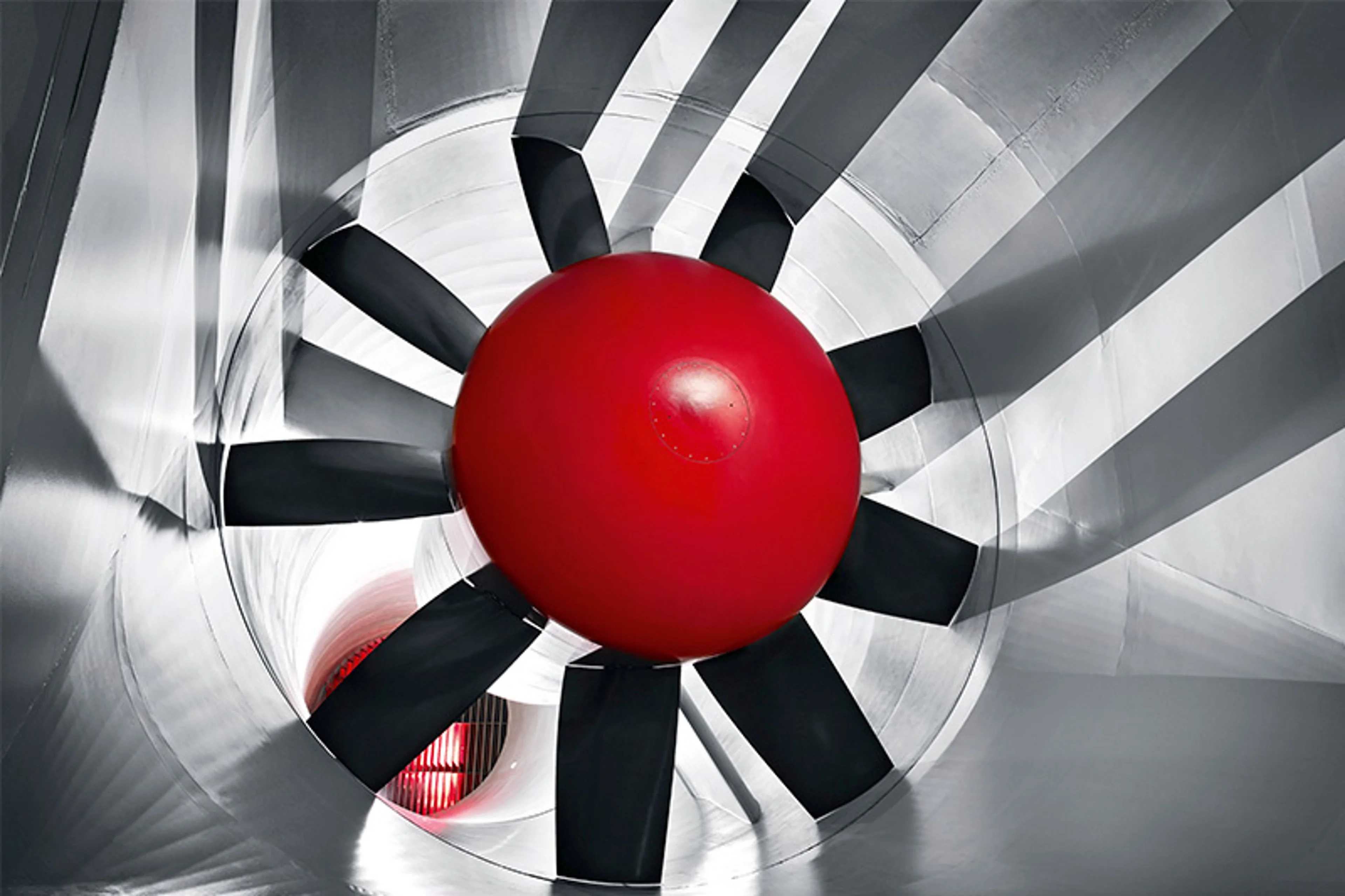

The giant fan in Volvo Cars Wind Tunnel

We're inside one of Volvo Cars' top-secret test labs. A steel-grey metal building in the east wing of the vast factory site on the island of Hisingen houses the company's legendary wind tunnel where some 20 people work under strict secrecy. For two to three years they test and analyse the new car models from early clay prototypes to the finished product.

The tunnel was already cutting edge when it was inaugurated in 1986. Since then, it has been refurbished and reengineered several times over to keep it state-of-the-art. Today, it is one of the most advanced wind tunnels in the world, permitting simulation of how a vehicle is impacted by wind speeds of up to 250 km/h and temperatures up to 60 degrees C. The large in-floor balance allows X-Y-Z directional forces to be measured, and changes in air resistance to be studied.

"It's unique in being both an aerodynamic wind tunnel and a heated climatic tunnel. We were also early-movers in building a system that provides a more precise picture of air resistance. Around 25 per cent of the air resistance occurs around the wheels, so being able to measure that is crucial," says Daniel Strömberg, who oversees the wind tunnel at Volvo Cars.

"Rain, snow, dust, dirt – we test everything that impacts vehicle road performance,"

Aerodynamic testing has become increasingly important in the automotive industry. Today, it is a crucial step in reducing emissions and fossil fuel consumption and constructing vehicles that are safe and balanced on the roads. As petrol and diesel vehicles are now increasingly being replaced by EVs, even a slight design adjustment to reduce air resistance by a few per cent may mean a huge difference in travel range.

"Wind testing is an incredibly powerful tool in vehicle optimisation. I remember this one car manufacturer who had no wing on the boot, which made the car unstable at high speeds," says Daniel as he pushes the button on a scale model of the tunnel that demonstrates how the air moves through guide vanes to a LEGO figure holding a flag blowing in the wind.

He was planning on becoming an aeronautical engineer, but the 9/11 attacks spelled the demise of the aviation industry. Happily, Daniel has now been with Volvo Cars for 20 years, the last 15 of which at the wind tunnel. He describes it as best job in the world, with tasks varying from service and methodology development to demonstrating the tunnel to everyone from school pupils to investors.

"The tunnel is manned from 06:00 to midnight Monday to Thursday and on Fridays and Saturdays we're operating from 06:00 to 18:00. That gives us a total of 96 test hours/week, and we're basically fully booked. When we're not testing our own vehicles, we're open to requests from other car brands, speed skiers, competitive cyclists or for traffic light testing. And the rock band Europe actually shot a music video here!"

A visit inside the test environment is like being let into a sci-fi film set. The 165-m-long tunnel curves in a loop and deep inside is an 8.15-m tall red and black fan with carbon fibre blades. The wind generated by the fan is turbulent, so it is fed through a series of chambers, structures and mesh screens to break down every vortex for smooth, laminar air flow. Finally, the wind reaches the last chamber, known as 'the contraction'.

"Inside the contraction, the wind speed increases six times over. If we run the fan at its max speed, we achieve 250 km/h in the test section, which is equivalent to 70 m/s, meaning an extreme hurricane. The vehicle is anchored to rolling steel belts and to the balance that measures the air forces. The balance is incredibly sensitive: you could weigh the ingredients for a sponge cake on it," says Daniel.

In addition to the aerodynamic tests, the facility also performs climatic tests. With the aid of a colossal heat exchanger and sun simulator, they can replicate driving in the hottest deserts, but also how the vehicle is impacted by various contaminants and pollutants.

"Rain, snow, dust, dirt – we test everything that impacts vehicle road performance," says Daryosh Farin, a contamination control engineer at Volvo Cars, "we make sure that dirt doesn't reach up to the door handle and that the view through the door glass is not obscured when driving in rain. If the customer doesn't notice anything at all that means we've done a good job."

Volvo Cars' wind tunnel is in operation virtually around the clock, year-round.

The tunnel's moving ground system is another major factor. Four flat steel belts set all the wheels spinning while a roller in the middle simulates the ground, and as it moves it draws air under the vehicle. Measuring wind with rotating wheels, as opposed to static ones, makes a big difference.

"We get a far more realistic picture because we can measure both rolling resistance and the force required to power the wheels and everything that spins along with them. We can also brake the car to simulate steep inclines or heavy towing, That way, we can really put the cooling systems through their paces," explains Max Sundén, energy efficiency specialist at Volvo Cars.

All the results are carefully analysed and compared with tests performed in both computer models and the real world. They then piece together a gigantic data puzzle. Just a single day in the wind tunnel might involve 100 different configurations, and tests on a new model are conducted for several years.

"On average, we reduce drag on the vehicle by more than 10 per cent. For EVs this is even more critical because if you're driving at 120 km/h, two thirds of the battery charge are used up by the drag. In this field, we work closely with the design team – there may be little details like the contouring of the rear lights or wing mirrors that need adjusting," explains Kaveh Amiri, an aerodynamics engineer at Volvo Cars.

We're about to experience the wind tunnel in practice. Daniel gives a signal to the control room and an alarm goes off. We hear a low rumble, after which a light breeze quickly increases to steady pressure between the walls. The wind is blowing at only 30 km/h, about 9 m/s, but the compact flow means that it feels like more.

Our hair flies up, paper whirls away.

"You can withstand 70 km/h, but you'll have to secure yourself with safety lanyards," shouts Daniel, beard fluttering in the wind. "If we power up the fan up to its max it runs on about 10 MW per hour, which is the annual consumption of a small detached house in Sweden, but the tests do also save a huge amount of energy. Personally, I can't get enough of the tunnel. Following and enhancing a new vehicle from the very first sketch is a real thrill."